Section 4

The Red Thread

So, when you tell your story, make sure that the user focuses on the story elements one at a time. When you transition from one element to the next, you should ideally connect these elements visually. Take a look at the first scene of our video again:

At the very beginning, the two circle-like shapes move to the center and shout ‘Hey, look here!’ – it’s exactly at this point that the text appears. The two circles then move below the text, as if to say ‘Let me show you where the next interesting bit of action will happen’. If you can find ways to guide your viewers’ focus like this, your animations will feel much more fluid and appealing.

Anticipation

Note that when the two shapes in the example above move from the title text to the place where the brain shape is about to show up, they don’t go there immediately. First, they move in exactly the opposite direction a little bit. This is called an anticipation – a little bit of animation that happens before the main action, and often sets up for this action in some way.

Here’s the same move without the anticipation.

In terms of focus, anticipation is a great tool for telling the viewer ‘hey, look at me, I’m going to do something exciting in a moment.’ The reason that we need this anticipation here is that after the text IN AFTER EFFECTS appeared, the viewer’s focus is on this text, not the circle shapes. So, we use this anticipation to return the viewer’s focus to the shapes before they begin their main movement. This way, the movement doesn’t come as a surprise and the viewer has time to focus on them before the action itself starts.

By giving the viewer these kinds of hints, i.e. where they should look next, you establish a relationship of trust. The viewer isn’t surprised by changes of focus, so they’re more relaxed and can follow along easier.

Connecting Scenes

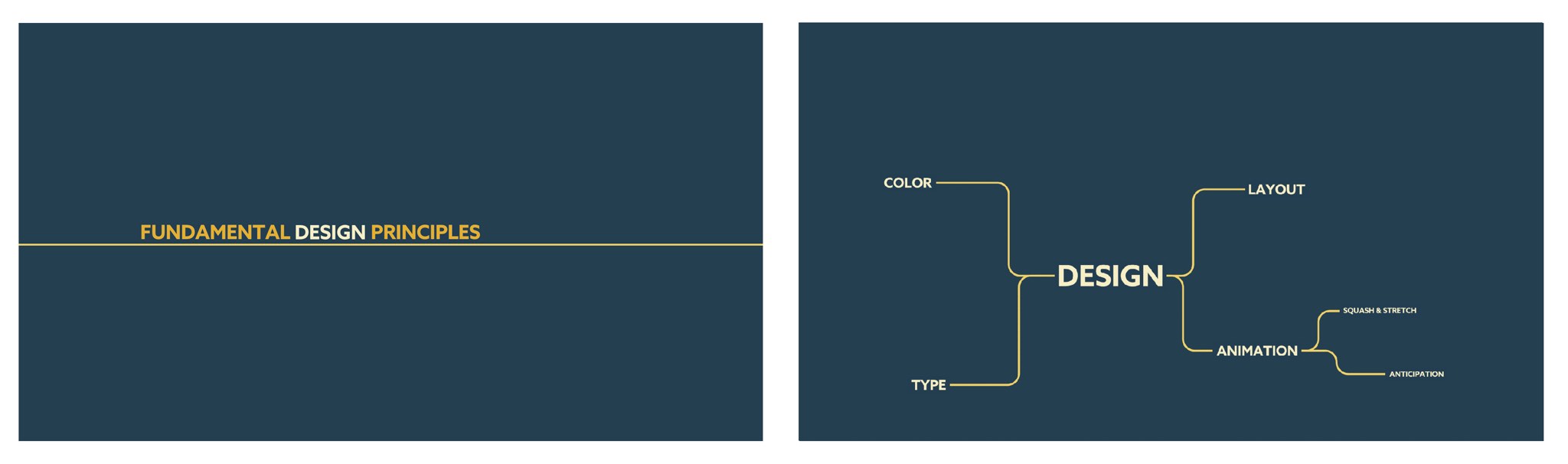

Let’s see how we can guide the viewers’ focus with a transition from the text Learn How and Why to the text Fundamental Design Principles.

Let’s start with a basic camera move to reveal the new content.

Let’s start with a basic camera move to reveal the new content.

To improve this transition, we should connect these two scenes in some way. One good solution for doing this is to make design elements from the second scene appear at the end of the first. In this example, we’ll use the line from the second scene, showing it at the end of the first scene before the camera move happens. To guide the viewers’ focus, we animate the line from left to right. That way we’re already shifting the viewers’ focus to the right side before the camera move starts.

This might seem like it’s a tiny difference. But in the first example of our transition, the camera move comes unexpectedly, taking the viewer by surprise. In the second variant, however, the viewer follows the movement of the line; when it touches the right side of the scene, they want to know where it’s going. So, now the camera move isn’t a surprise – it’s exactly what the viewer wants to happen next.

Breaking the Rules

We’ve just learned that viewers are happier if you guide their focus, making sure they always know in advance where to look next. But have you ever felt the exciting tension of watching a fireworks display and not knowing quite where the next big explosion will happen? Surprises can be good, and it’s OK to break the rules from time to time.

In this transition, there’s a chaotic jumble of letters entering and leaving the scene at the same time. There’s so much happening at once that you don’t know where to look. Did you feel a tiny bit of confusion when watching this part for the first time? And wasn’t it kind of a relief when the letter chaos finally turned into a readable text? Making the focus briefly unclear can add excitement, but these moments should never last too long, or otherwise you’ll frustrate or stress the viewer.

Two Read Threads are too much

Let’s take a look at one more transition example, between these two parts: Since both scenes contain yellow lines, my first idea was for the line from the first scene to become one of the lines in the second scene. At the same time, the word DESIGN from the first scene could move to its location in the second design, while the remaining text disappears. The result looks like this:

Since both scenes contain yellow lines, my first idea was for the line from the first scene to become one of the lines in the second scene. At the same time, the word DESIGN from the first scene could move to its location in the second design, while the remaining text disappears. The result looks like this:

The problem with this animation is that the line and the text compete for the viewers’ attention. When watching the scene, your eyes follow the line, so when the interesting text move happens, your focus is still on the line and you miss it. You have to decide – either focus clearly on the line, or on the text. Both together will never work. So, I decided that the text was way more important for the story, and made sure that the viewer focuses on it.

To keep their focus on the text, I first removed the distracting line animation completely. The line disappears very fast, so it’s almost unnoticed, while at the same time we animate a circular line around our text to make it really clear where the focus should be. These kinds of design elements are frequently used as focus guides in motion graphics, and come in all kinds of flavors.

Split text layers into characters, words, lines and more. The placement of each character is accurately preserved without expressions, text animators or other tricks.

After camera tracking set the ground plane of your scene and orient everything accordingly.

Join our newsletter for updates on this book and more great stuff we create!